Aspergillus is a common saprophytic fungus of the class Plectomycetes.

The name Aspergillus is adapted from the Latin name Aspergillum, which means holy water sprinkler. As the fungus has a sprinkler-like appearance when viewed under a microscope.

Occurrence of Aspergillus

Aspergillus is a genus of about 132 species (Sarbhoy, 1985). It occurs in all parts of the world.

Most of the species are saprophytes, growing on decaying fruits, vegetables, bread, jams, jellies, butter, leather, fabrics, etc. Some species (e.g., A. fumigatus) can also grow on soil.

Aspergillus niger is the most common species, and it is popularly known as black mould.

A few species of Aspergillus, such as A. flavus, A. niger, and A. fumigatus, are parasites on animals and humans and cause aspergillosis, a group of lung diseases.

- Some Aspergillus species are: A. repens, A. niger, A. favus, A. herbariorum, A. fumigatus, etc.

Vegetative Structure of Aspergillus

The vegetative plant body of Aspergillus is the mycelium. It consists of well-developed, profusely branched, thin-walled, slender, septate hyphae. The hyphae may be hyaline or pale-coloured.

Some of the hyphae ramify superficially over the substratum, while others penetrate deep into the substratum for the absorption of nutrients.

The hyphal cells are multinucleate. Each cell has a thin cell wall that surrounds the granular cytoplasm.

The cytoplasm contains many cellular organelles, such as mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum, ribosomes, vacuoles, etc. The reserve food material is the oil globules present inside the cytoplasm.

The cytoplasm of the adjacent cells remains continuous through the small pores in the septa (i.e., dividing walls between cells).

Read also- Penicillium: Occurrence, Structure, Reproduction

Reproduction in Aspergillus

Aspergillus reproduces in all three methods: vegetative, asexual, and sexual.

Vegetative Reproduction

Vegetative reproduction in Aspergillus occurs through fragmentation and sclerotia.

Fragmentation

The vegetative mycelium can break into small fragments due to accidental breakage. Each fragment develops into a new individual under favourable conditions.

Sclerotia

In extreme environmental conditions, some Aspergillus species, such as A. terreus and A. niger, form sclerotia. These are the hard masses of hyphae containing sufficient food reserves.

Sclerotia remain dormant until suitable conditions return.

Asexual Reproduction

Asexual reproduction is more common in Aspergillus. It takes place through the formation of conidia on conidiophores.

Some hyphal cells grow more rapidly, become long and thick-walled. These cells are called foot cells.

From each foot cell arises a special erect branch as an outgrowth, known as a conidiophore. The conidiophores are thick-walled, aseptate, and unbranched.

The tip of each conidiophore swells up into a bulbous head called the vesicle. It is multinucleate and develops many radially arranged tubular outgrowths, the sterigmata or phialides.

Each sterigma is uninucleate and bottle or finger-shaped. In some species, a second layer of sterigmata develops on the apical part of the primary sterigmata, called secondary sterigmata.

From the tip of each sterigma, a chain of conidia is produced.

Formation of Conidia

Initially, the sterigma elongates at the tip to form a tube. The single nucleus of the sterigma divides mitotically into two daughter nuclei. One of the daughter nuclei migrates into the tube and forms the first conidium by cutting off the apical portion of the tube.

After the formation of the first conidium, the upper broken wall of the sterigma functions as a cap around it. The second conidium is formed from the sterigma just below the first conidium.

The process continues, and as a result, a long chain of conidia is formed at the tip of each sterigma. The conidia are thus arranged in basipetal succession (the oldest conidium appears at the top and the youngest one at its base).

Structure and Germination of Conidia

The conidia (also called phialospores or phialoconidia, as they arise from the phialides) are small, unicellular, uninucleate, and oval or spherical in shape. They are black, brown, yellow, or green in colour.

Each conidium has a two-layered wall. The outer exosporium is thick and ornamented, while the inner endosporium is thin and delicate.

In many species, the nucleus in conidia divides repeatedly, and they become multinucleate.

The conidia are disseminated by the wind and germinate by producing germ tubes on a suitable substratum. Each germ tube later develops into a new mycelium.

Sexual Reproduction

The perfect stage, or sexual stage, occurs rarely in Aspergillus.

Most of the species where sexual reproduction has been observed are homothallic. However, heterothallism occurs in a few species (e.g., A. heterothallicus and A. fischerianus).

The male sex organ is called the antheridium, while the female sex organ is known as the ascogonium.

The ascogonium is well developed and functional. But the antheridium is absent in some species, or if present, it is functionally inactive. The species of Aspergillus thus show variation in their sexual behaviour.

Ascogonium

The ascogonium develops on a special hyphal branch called the female branch. Soon, the female branch becomes septate and loosely coiled, which is now called the archicarp.

The young archicarp is differentiated into three parts: a basal multicellular, multinucleate stalk; a middle unicellular, multinucleate ascogonium; and a terminal unicellular, multinucleate receptive organ known as the trichogyne.

Initially, the archicarp is loosely coiled, but later on, the coil becomes dense and looks as a cork screw-like structure.

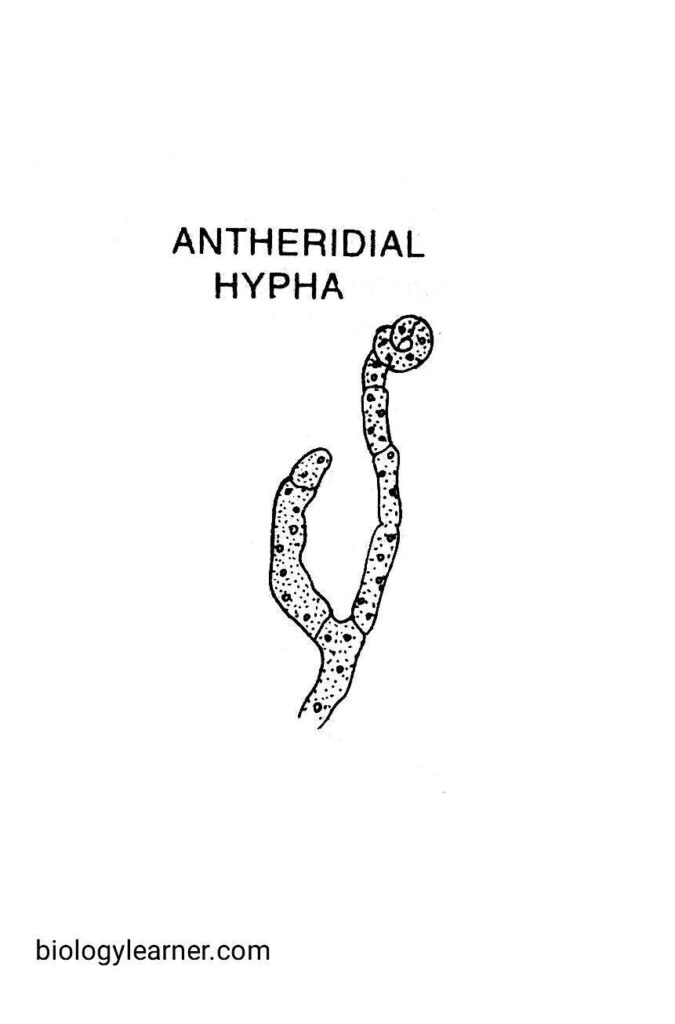

Antheridium

The development of antheridium initiates just before or during the separation of the ascogonial hypha. It develops on the same hyphae from which the ascogonium develops or on adjacent hyphae of the same mycelium.

The antheridial branch, also known as pollinodium, cuts off an apical antheridium, which is slightly broader. The lower remaining portion is called the stalk. The antheridium and the stalk are both unicellular and multinucleate.

Finally, the pollinodium gets coiled around the archicarp and arches over the apex of the ascogonium.

Fertilization

The tip of the antheridium comes into contact with the apical point of the trichogyne. The common wall dissolves at the point of their contact, and the contents of the antheridium pass to the ascogonium through the trichogyne (plasmogamy).

The male and female nuclei form pairs in the ascogonium. These paired nuclei are called dikaryons.

In some species (e.g., A. repens), the antheridium is well developed, but the male contents do not transfer to the ascogonium. In some other species (e.g., A. fischerianus, A. flavus), the antheridium is completely absent. In such cases, the pairing occurs between ascogonial nuclei.

Soon after, the ascogenous hyphae are developed from the fertilized ascogonium.

Development of Ascus and Ascocarp

After the formation of dikaryons, the ascogonium becomes septate. The cells are also binucleate, contain both male and female nuclei in each of them. These dikaryotic cells give rise to the ascogenous hyphae.

The transverse walls appear, and the hyphae become multicellular. The terminal cell of each ascogenous hypha elongates and curves to form a hook-like structure called the crozier.

The two nuclei in the dikaryon divide to form four daughter nuclei. The four daughter nuclei are arranged in three cells in the crozier. These three cells are a uninucleate terminal or ultimate cell, a binucleate penultimate cell (which occurs at the curve position), and a uninucleate basal or stalk cell.

The penultimate cell now functions as an ascus mother cell. The two nuclei in the ascus mother cell fuse to form a diploid nucleus (karyogamy), and thus a young ascus is formed.

The diploid nucleus divides by meiosis and then mitosis to form eight haploid nuclei. Each of the nuclei transformed into an ascospore.

Simultaneously with the development of ascogenous hyphae, a large number of sterile branches also develop from the base of the archicarp. These sterile hyphae form a two-layered protective covering called the peridium.

The entire structure is called an ascocarp, i.e., fruit body. The ascocarp appears as a hollow ball. Such a type of ascocarp is known as the cleistothecium (completely closed fruit body).

The mature cleistothecium is yellow in colour. It encloses many globose or pear-shaped asci. Each ascus contains eight ascospores.

Ascospores

The ascospores are haploid, uninucleate, and wheel-shaped. They are very small, 5 μ in diameter.

Each spore remains surrounded by two wall layers. The outer epispore is thick and sculptured, while the inner endospore is thin.

Liberation of Ascospores

At maturity, the walls of the asci dissolve, and the ascospores are set free in the cleistothecium. Finally, ascospores are liberated from the cleistothecium after the decay of the peridium wall.

Under favourable conditions, each ascospore germinates into a germ tube, which develops new mycelium.

Taxonomic Position of Aspergillus

| Division: | Eumycota |

| Sub-Division: | Ascomycotina |

| Class: | Plectomycetes |

| Order: | Eurotiales |

| Family: | Eurotiaceae |

| Genus: | Aspergillus |